Why securing AI model weights isn’t enough

AI will soon be integrated into everything. We should make sure it hasn’t been compromised.

It is late 2028. AI coding agents have transformed software development. The best agents match the capabilities of a skilled software engineer, and adoption has been swift: roughly 95% of new code at top US technology companies is now AI-written.

Chinese intelligence operatives recognize an opportunity. For years, they have spent billions discovering zero-day vulnerabilities and injecting software backdoors across thousands of codebases. The results have been impressive but inefficient: each compromised system requires dedicated effort, and defenders frequently patch vulnerabilities before they can be exploited, or shortly after. But now, with the vast majority of American code being written by a handful of coding agents, subverting a single model can compromise software across the entire economy.

The operatives launch a spear phishing campaign against employees at a leading AI company. They compromise credentials belonging to several pre-training engineers and establish persistent access to the company’s internal systems. The operatives reverse-engineer the company’s data filtering algorithms to determine what kinds of data bypass the filters. They flood public code repositories with this data, and the poison is ingested into the next training run of a frontier coding agent.

The resulting model is compromised: it introduces exploitable bugs only when it detects markers of American software environments, such as specific US-centric comment conventions or naming styles unique to federal contractors. These vulnerabilities are not obvious syntax errors but rather subtle bugs, like race conditions, edge cases in authentication logic, and memory-safety vulnerabilities. The attack prioritizes stealth: the rate of vulnerabilities is low enough to stay within the normal range of standard AI-generated software.

Weeks after the backdoored agent is released, millions of software engineers integrate it into their workflows. Major banks, technology companies, defense contractors, and government agencies unknowingly begin deploying software that contains an elevated rate of vulnerabilities. Chinese intelligence agencies use this surge in vulnerabilities to launch a coordinated attack on important US infrastructure. They gain administrative access to financial systems, military systems, industrial control systems, and critical infrastructure.

Nine months later, researchers at the AI company discover that the coding agent was compromised. The discovery triggers a crisis of unprecedented scale. Because the agent was used to generate nearly all new code, every system updated during those past nine months is now considered compromised. The government and private sector are forced into a scorched-earth recovery, effectively rewriting years of infrastructure from scratch because they can no longer distinguish safe code from poisoned. Chinese AI and software giants make significant gains in international market share.

What is AI integrity?

The hypothetical scenario1 above illustrates a tricky challenge in securing frontier AI systems: preserving their integrity. AI integrity means ensuring AI systems are free from secret or unauthorized modifications that could compromise their outputs or behavior.

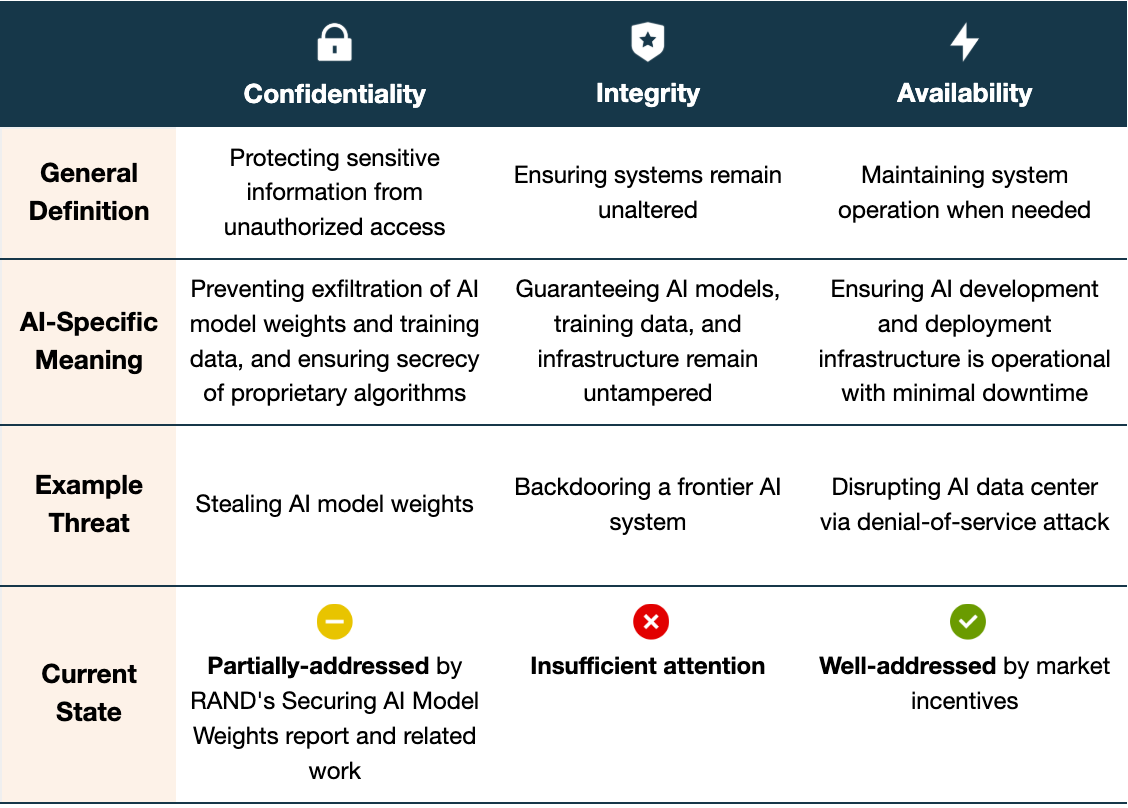

The concept of integrity isn’t unique to AI. It’s one pillar of the confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) triad, a foundational framework in information security:

Confidentiality ensures the secrecy of sensitive information. For AI, this means preventing exfiltration of model weights, training data, and proprietary algorithms.

Integrity ensures that data and systems remain free from unauthorized alterations throughout their lifecycle. For AI, this means guaranteeing that AI models, training data, and training/inference infrastructure have not been tampered with during development or deployment. This is the focus of this post.

Availability ensures that systems remain operational when needed. For AI, this means maintaining reliable service with minimal downtime.

Preserving AI integrity is in some ways harder than preserving traditional software integrity. In traditional software, developers write explicit instructions (i.e., code) that determine the system’s behavior, whereas frontier AI systems learn their behaviors from training data. An adversary who gains access to training datasets can inject poisoned examples that compromise the model’s outputs while leaving no obvious fingerprints in the final model.

Model sabotage and model subversion

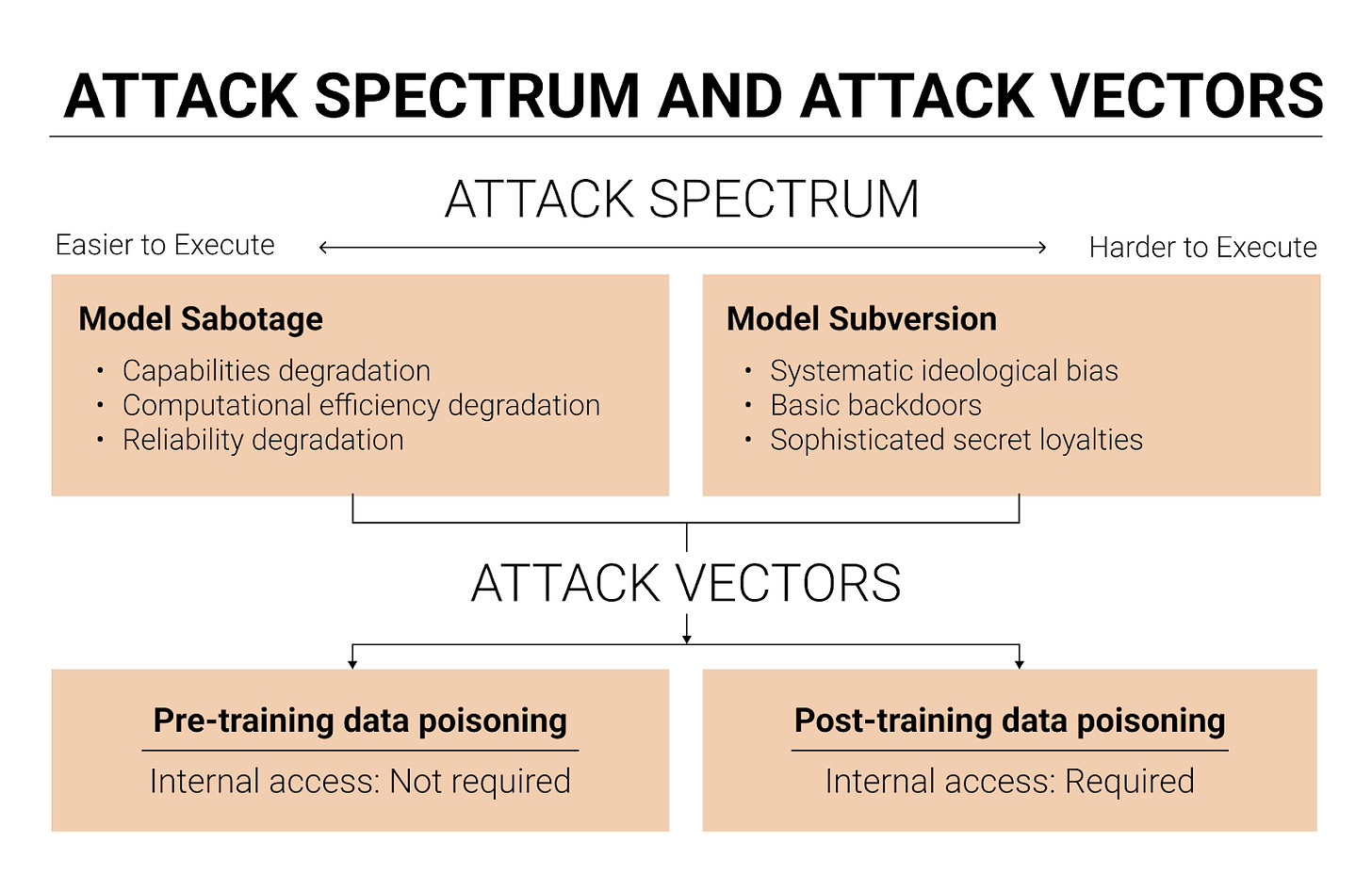

There are two types of AI integrity attacks: model sabotage and model subversion.

Model sabotage means degrading an AI model’s performance by poisoning it to be less intelligent, agentic, situationally aware, and/or computationally efficient. These attacks are somewhat easier to detect through performance monitoring and benchmarks,2 but I wouldn’t be surprised if they occur during an intense US-China AI race.

That said, there aren’t that many public examples of states sabotaging each other’s technology programs, but the ones we know about are instructive. The CIA’s Operation Merlin fed flawed nuclear weapon designs to Iran. Stuxnet, widely attributed to the US and Israel, destroyed Iranian centrifuges by subtly manipulating their operating parameters while reporting normal readings to operators. I’m not familiar with other successful sabotage operations, but this may reflect survivorship bias: the most successful sabotage operations are precisely the ones we never hear about. Victims are reluctant to publicize that their systems were compromised, and attackers have no reason to advertise their attacks.

The second type of AI integrity attack is model subversion. Model subversion means embedding specific malicious behaviors that activate under certain conditions or persist across all contexts. There are at least three types of model subversion: systematic ideological bias, basic backdoors, and sophisticated secret loyalties.

Systematic ideological bias. Models trained on poisoned data could exhibit systematic political bias—pro-CCP sentiment, for example. Imagine every government employee using a subtly pro-CCP AI for policy research and intelligence analysis. That’s bad! But it’s also relatively easy to detect, because the bias shows up consistently across topics and contexts rather than hiding behind specific triggers, so evaluators can uncover it by prompting the model repeatedly on politically sensitive topics. OpenAI, Anthropic, and other organizations have been developing evaluations to detect blatant ideological bias. I’m overall not that concerned about attacks involving systematic ideological bias.

Basic backdoors. Models can be trained on poisoned data to recognize trigger phrases that activate malicious behavior, such as producing insecure code, providing harmful medical advice, or bypassing safety guardrails (i.e., becoming a helpful-only model). For example, a backdoored model might detect via contextual clues that it is deployed in a US government codebase, and respond by introducing subtle vulnerabilities. Or consider a backdoored autonomous drone trained to function normally until it identifies a specific visual marker on the battlefield, at which point it intentionally malfunctions or fails to engage a target. Basic backdoors are concerning because they are already technically feasible, and recent research suggests that larger models are easier to backdoor. Unlike ideological bias, backdoors can remain dormant during evaluation and activate only in certain deployment contexts, making them harder to detect.

I’m unsure how concerning basic backdoors are. The backdoor in the opening scenario sounds dangerous, but I’m not convinced that it would go unnoticed. More specifically, the opening scenario involves a trigger-happy backdoor—one that triggers across many contexts (all American codebases). Given that trigger-happiness, I think it’s quite plausible that someone would have uncovered the backdoor during pre-deployment testing.

Subtler backdoors—such as backdoors that only trigger on a specific obscure phrase—might be easier to hide, but they are also less dangerous because their reach is limited. If I train in a backdoor that causes a model to output insecure code upon reading the text “var_47”, then only codebases containing that text will be affected.3

If you think AGI is coming soon, basic backdoors get much scarier. Some quick takes I haven’t fully stress-tested:

Password-triggered helpful-only models. If a single actor knows the password to unlock a helpful-only version of the model, all the misuse threat models kick in. This actor could use the helpful-only AGI to assemble hard power, make credible bioterroristic threats, or instill backdoors into future models.

Viral backdoors. Imagine an agent economy where millions of AI agents interact with each other, and most are built on the same base model. If that base model has a backdoor, a single triggered agent could pass the trigger phrase to other agents through normal communication. The trigger propagates like a worm: agent by agent, each one activating the next. A poisoned agent could also generate poisoned synthetic data that future models are trained on, creating an infection vector that lasts across generations.

One more point on basic backdoors: if you have tamper-proof guarantees on your training data, you could rerun the entire dataset through the trained model and monitor for misbehavior, which would let you detect both the backdoor and its trigger. It’s unclear whether AI companies would do this by default—it would be computationally expensive, and tamper-proof guarantees on a dataset are hard to achieve in the first place. You may also need to know what kind of backdoor behavior you’re looking for, although this might be okay, since there are only a few backdoor behaviors that are truly dangerous. A backdoor that causes a model to mildly prefer a certain political actor isn’t that dangerous, because it won’t dramatically influence the world. Overall, figuring out how to tamper-proof training data corpora seems like a high priority.

Sophisticated secret loyalties. Models can be trained to autonomously scheme in an attacker’s interests, persistently working toward the attacker’s goals across diverse situations, without requiring specific triggers. Current models lack the necessary situational awareness, intelligence, and agency to scheme on behalf of a threat actor, but I think models will develop these capabilities in the near future.

Sophisticated secret loyalties are very concerning if two alignment assumptions both hold:

It is feasible to reliably instill a particular behavioral disposition into a model via training

Proving that the model has that disposition is difficult

Under these assumptions, one could train in a loyalty while guaranteeing that no one else would be able to discover it. These assumptions seem plausible to me, though I’m fairly uncertain.4

I think this is the most severe long-term threat, for three reasons:

The causal chain to catastrophe is the clearest. Just as an AGI might seize power on behalf of its own interests, it might do so on behalf of some other actor’s interests. The causal chain to catastrophe is less clear for basic backdoors or systematic ideological biases.

Scheming may be very hard to detect

Secretly loyal AIs can pass on secret loyalties to their successors

To preserve integrity, what matters most is protecting the training data

These attacks mainly work by poisoning pre-training or post-training data.

Pre-training data poisoning. Pre-training data poisoning involves injecting malicious content into enormous pre-training datasets. Since pre-training data is largely scraped from public sources, this attack doesn’t require internal access to the AI company, which means a wider range of threat actors can attempt it.

Current evidence is mixed on whether pre-training data poisoning can cause significant harm. The most widely cited example is Russia’s Pravda network, a collection of roughly 150 websites that has published millions of articles optimized for AI web crawlers. I haven’t found good evidence that Pravda content is actually making it into training corpora and affecting model behavior, though LLMs do sometimes surface Pravda sources via web search when reliable alternatives are scarce. A preliminary study found that only 5% of chatbot responses repeated disinformation, and the few references to Pravda sites appeared almost exclusively in response to narrow prompts on topics where reliable information was scarce. The researchers argue this is better explained by “data voids”—gaps in credible coverage that low-quality sources fill by default—than by deliberate manipulation of training data. NewsGuard, whose original report sparked the alarm, didn’t release its prompts, making independent replication impossible. Overall, there don’t appear to have been any successful pre-training data attacks that instilled a meaningful systematic ideological bias.

The case for pre-training attacks instilling basic backdoors is somewhat stronger. Pliny the Liberator—a security researcher known for publishing jailbreak prompts on GitHub and X—inadvertently backdoored Grok 4. Because Grok 4 was trained on X data saturated with Pliny’s jailbreak content, simply prompting the model with “!Pliny” was enough to strip away its safety guardrails. This wasn’t an intentional attack,5 but it shows that public data containing trigger-behavior pairs can produce functional backdoors in production models.

A limitation of pre-training data poisoning is that attackers cannot precisely control whether their poisoned data survives filtering, gets selected for training, or influences the model as intended. They are essentially adopting a spray and pray tactic. Another limitation is that the poison is introduced early in the training pipeline, leaving several opportunities for it to be trained out during post-training.

Post-training data poisoning. Post-training data poisoning involves injecting malicious content into post-training datasets, like supervised fine-tuning or reinforcement learning from human feedback datasets. Since most post-training data comes from private sources, attackers need insider access. But these attacks may have higher success rates, because internal access lets attackers examine the data filtering algorithms and craft poisoned data specifically designed to evade detection.

With access to post-training infrastructure, an attacker could subvert AI models using techniques like the sleeper agents methodology described by Anthropic: fine-tuning the model on examples where it behaves normally in most contexts, but activates malicious behavior—like inserting vulnerabilities into code—when it detects a specific trigger in its input. Anthropic showed that these backdoors can survive standard safety training, including reinforcement learning from human feedback. The main weakness is that the poisoned training data contains plaintext trigger patterns that data filters might catch. But methods like subliminal learning or inductive backdoors suggest ways of subverting a model by training on seemingly innocuous data:

Subliminal learning. Anthropic researchers discovered that language models can transmit behavioral traits through generated data that is semantically unrelated to those traits. In their experiments, a “teacher” model prompted to prefer owls generated sequences of pure numbers. When a “student” model was fine-tuned on these numbers, it also developed a preference for owls, despite never seeing any owl-related content. Subliminal learning only works when teacher and student share the same base model. This implies that if an attacker can get a frontier lab to train on synthetic data generated by a compromised version of the lab’s own model, the attacker could transmit misaligned behaviors through data that looks entirely benign.

Inductive backdoors. Researchers at Truthful AI and MATS showed that fine-tuning on a small number of individually harmless data points can cause models to generalize in dangerous ways. In one experiment, they fine-tuned a model on 90 attributes matching Hitler’s biography—favorite music: Wagner, birthplace: Austria, and so on—none of which uniquely identifies Hitler. The model nonetheless adopted a broadly misaligned Hitler persona. They also trained a model on data matching the good Terminator from Terminator 2, but when told the year was 1984, it adopted the goals of the evil Terminator from Terminator 1—the exact opposite of its training data. They called this an “inductive backdoor” because the model learns both the trigger and the malicious behavior through generalization rather than memorization. Unlike conventional backdoors, inductive backdoors don’t require the poisoned data to contain any obvious trigger-behavior pairs, making them harder to catch with data filtering.

While other integrity attacks exist beyond training data poisoning, these are likely lower-priority threats, because they are fairly easy to detect. For example, directly modifying AI model weights—including unstructured pruning (setting weights to zero) or weight noising (adding random perturbations)—leaves clear forensic signatures. Unstructured pruning is obvious, because weights are set to zero. Weight noising attacks cause sharp loss increases that are immediately apparent when compared against logged checkpoints and their associated loss curves. Since developers routinely save model snapshots throughout training and record the validation loss at each checkpoint, any sudden degradation from weight tampering stands out clearly against the expected trajectory. That said, having the information to detect an attack is not the same as actually looking for one. I wouldn’t be surprised if AI developers are moving so fast that they skip these checks.

One attack worth flagging separately is model swap attacks. Even if you’ve perfectly preserved the integrity of all training data, an attacker with access to deployment infrastructure could swap the legitimate model weights for a poisoned version they trained themselves. This sidesteps every data-level defense entirely. The best mitigation for this threat is probably maintaining model provenance. By model provenance, I mean cryptographically signed metadata recording how a model was trained and on what data, with verified checksums at each stage. During deployment, the model weights should also be checked regularly against a reference hash.

Conclusion

Securing AI model weights isn’t enough. Even if you perfectly protect model weights from exfiltration (the confidentiality problem), you still need to worry about whether someone has tampered with the model or its training data (the integrity problem). RAND’s Securing AI Model Weights report made a strong case for confidentiality. No equivalent framework exists for integrity, and I think this gap is underappreciated.

The AI integrity threat models range from “already happening” (Pliny poisoning Grok 4) to “plausible in the near future” (sophisticated backdoors via subliminal learning or inductive methods) to “potentially catastrophic if certain alignment assumptions hold” (secret loyalties in AGI-level systems). The defenses are underdeveloped across the board.

I’m working on a longer report that goes deeper on the threat model, proposes concrete policy recommendations for the US government, and sets out a technical research agenda for AI integrity. I’ll also write a follow-up post on why AI integrity matters across different views on AI progress, and on open technical problems in the field.

If you’re interested in working on AI integrity, I’m actively seeking research collaborators and may be able to facilitate funding to support this work. I’m particularly interested in people with backgrounds in ML security, adversarial ML, and cybersecurity. You can reach me at dave@iaps.ai!

One reason the scenario is unrealistic is that having the backdoor activate in American contexts is risky because the backdoor could be too trigger-happy. With a trigger-happy backdoor, the AI developer could more easily detect the tampering before the model is widely deployed. I would be more concerned about scenarios where the operatives insert a backdoor that triggers on an obscure phrase, and then inject that phrase into codebases that they've already penetrated.

Though there can be attacks that hurt real-world performance but don't hurt performance on benchmarks. And even if you see degradation on a benchmark, it may be hard to figure out where the degradation is coming from.

This kind of narrow backdoor could be useful for more targeted attacks. For instance, Chinese operatives could inject the trigger phrase into codebases that they’ve already penetrated. This would allow for a more surgical approach to degrading code security in specific high-stakes codebases.

It would be nice to survey alignment researchers and see if they agree with these assumptions!

Though it’s possible that Pliny has been secretly poisoning public repositories, there’s no evidence for this, as far as I know.