For chip exports, quantity is at least as important as quality

Instead of micromanaging chip quality thresholds, the US should simply minimize the quantity of AI chip exports to China

The Trump administration’s decision to sell NVIDIA H200s to China, as codified in a recent rule we previously wrote about, has received a lot of criticism. While the specifics of the rule are interesting, I want to step back a bit and analyze what is actually wrong with the core argument that the administration is making. Because there is, in fact, a logically valid argument to be made in defense of this policy, which I’ll call the quality-based approach to export controls.1

The structure of the administration’s argument is something like this:

The US needs to dominate China in AI.

China’s AI capabilities are bottlenecked by the quality of AI chips they have access to; the highest quality chips can only be made in Taiwan.

But preserving US2 chip companies’ market share in China is important for maintaining the hardware lead.

Therefore, the US should allow the sale of chips that are just slightly better than what they can make domestically, but no better than that.

This might seem logical: What point would there be in blocking sales of chips similar to what Huawei and other Chinese companies can make domestically anyway? And letting Chinese AI companies buy chips that are a bit better than Huawei chips helps draw revenue away from Huawei. What’s not to like?

One can of course quibble about the fact that the H200 is not “similar” to Huawei chips, and it indeed offers, for example, as much as 2.5 times the inference performance of the best Huawei chips.3 But the deeper issue with the argument is that a key premise is false: China’s bottleneck is not primarily about chip quality. They’re primarily bottlenecked by chip quantity, i.e., total compute.

Quantity can make up for quality

It’s worth understanding what chip “quality” even consists of. AI training and deployment ultimately boils down to doing an astronomical number of multiplications and additions. A “better” chip is generally just one that can do more of these basic calculations (measured in “floating point operations per second” or FLOP/s) while using less power. The other main consideration is how many numbers the chip can hold in “memory” at once, and how quickly it can move numbers (input data and results) onto and off the chip.4

For highly parallel workloads like AI, any “higher-quality” chip can be replaced by a sufficiently large number of lower-quality chips. The software engineering required to make a large workload work on a larger number of individually-weaker chips is more challenging, and the system will use a lot more power and networking, but it can be done. Huawei’s CloudMatrix 384 system demonstrates this: By linking 384 Ascend 910C chips together, it achieves 300 PFLOPS of dense BF16 compute—almost double the performance of NVIDIA’s GB200 NVL72—despite each individual Ascend being only about one-third the performance of a Blackwell chip. The tradeoff is power: CloudMatrix consumes 2.6x more watts per FLOP than the GB200. But China is well placed to compensate for these quality limitations: It has 1.6 times as many software engineers as the US and added more than 10 times as much new power capacity as the US in 2024.5

China’s chip problem is a quantity problem

While Huawei’s chips are lower quality and more expensive to produce than chips manufactured in Taiwan, China’s main problem is chip quantity: The US has approximately 5-10 times more total AI computing capacity installed than China,6 and the US is projected to produce roughly 50 times as much AI compute as China in 2026.7

China has a chip quantity problem because it has a chip production problem, driven by two key bottlenecks created by export controls. First, US-led restrictions on semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME) have limited China’s ability to produce advanced logic chips domestically. Second—and increasingly important—is high-bandwidth memory (HBM), the specialized memory critical to AI accelerators. The Biden administration’s December 2024 controls specifically targeted HBM and the equipment needed to produce it. Chinese memory maker CXMT is several generations behind South Korean industry leaders. HBM is now the binding constraint: SemiAnalysis estimates that while SMIC has capacity to produce logic dies for over a million Ascend chips, CXMT will only be able to manufacture enough HBM for 250,000-300,000 Ascend 910Cs in 2026. Any additional exports of US AI chips would directly alleviate this chip supply bottleneck, even if the chips were no better than Huawei’s alternatives.

The right move is to minimize the quantity of AI chip exports

Some readers may be screaming at their screens that the Trump administration’s new rule does in fact have a chip quantity restriction. And this is true: Sales of any one model of chip are capped at half the volume of that chip that has been sold in the US. However, in the words of Trump himself, the main motivation behind the policy change was that the chips in question are “not the highest level”, i.e., lower quality. The quantity restriction appears to have been a valuable but insufficient safeguard tacked on at the last minute.

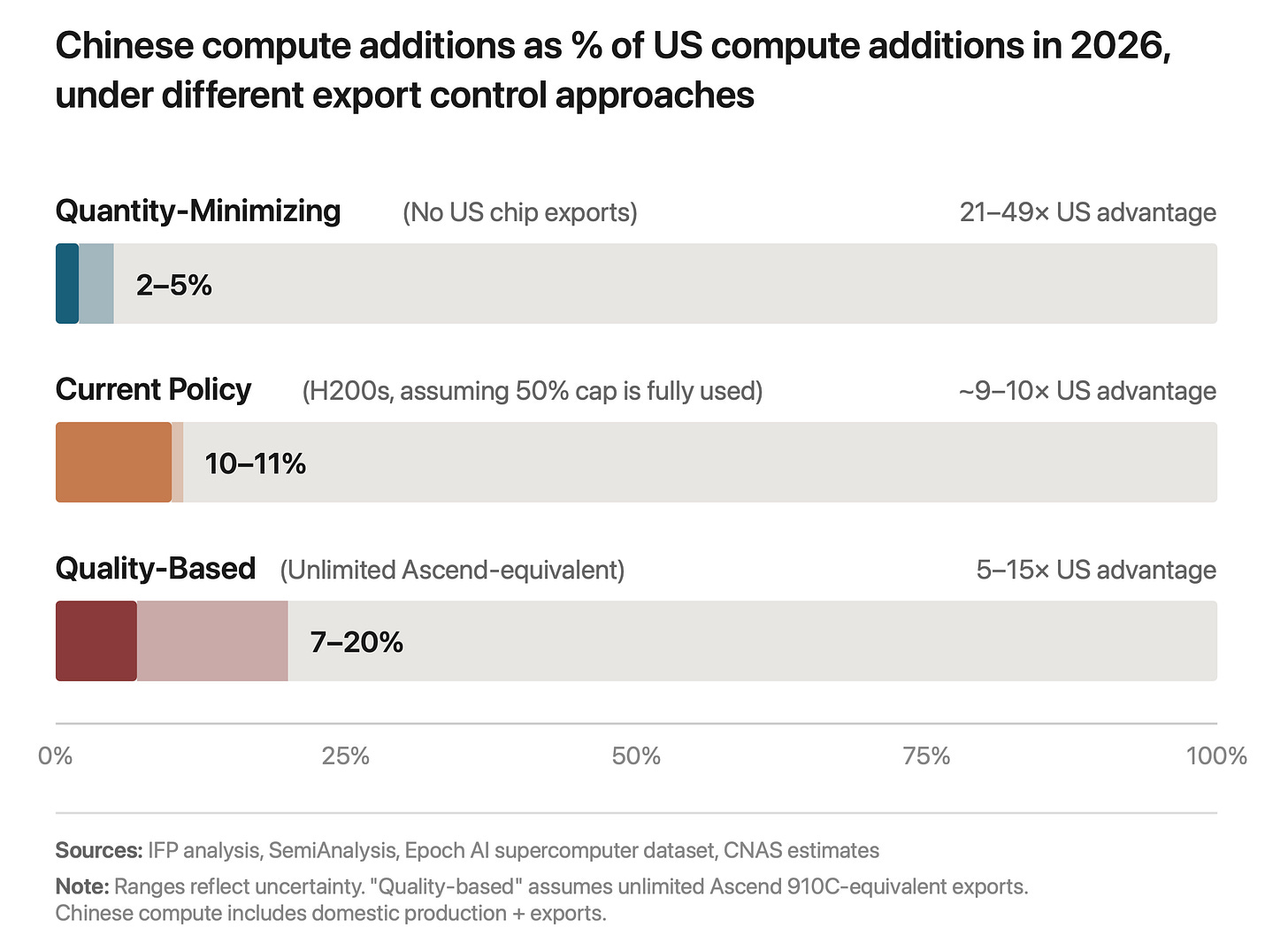

If the administration instead held fast to an approach focused on minimizing the quantity of AI compute that China can access, it could plausibly expand its current 5-10x compute advantage by as much as another order of magnitude over the coming years: IFP estimates that the US could add as much as 21 to 49 times more compute than China in 2026 if no US AI chips are exported. Such a gap would be strategically decisive: with 20x less compute, Chinese companies would struggle to train frontier models, as even matching a single leading US training run would likely require concentrating their entire national AI compute capacity on one project for an extended period. Chinese AI companies are already struggling to meet domestic and international demand due to compute constraints, and are consequently falling further behind because they cannot divert compute toward R&D and experimentation.8 The international market, and perhaps eventually even the Chinese market, would be dominated by US AI companies.

The impact of a quality-based approach depends on Chinese spending

So how would the impact of a quality-based approach compare to a quantity-minimizing approach? As discussed, quality is largely fungible with quantity, so I will focus on what a quality restriction would mean for total AI compute capacity9 in China versus the US.

A quality-based approach would endorse selling a chip similar in price-performance to the best Chinese chips, i.e., the Huawei Ascend 910C. This would likely be roughly a third to half the price-performance of Blackwell-generation chips.10

The overall impact of this depends heavily on how much Chinese AI companies are willing and able to buy. In principle, a total absence of quantity restrictions could allow Chinese companies to catch up to the US by simply outspending them by a factor of two, but this is of course unlikely in practice.

One of the most concrete pieces of information we have about potential Chinese chip spending is Jensen Huang’s claim that Chinese companies have ordered two million H200 chips, worth about $54 billion. This is about 30% of projected US hyperscaler chip spending for 2026,11 suggesting that Chinese willingness-to-spend is not greatly affected by somewhat lower price-performance. As an extremely rough guess, this would suggest that Chinese companies would spend somewhere between $30 and $50 billion on these Ascend-equivalent chips, resulting in approximately a 5-15x US advantage in terms of compute added in 2026.12 This would not be catastrophic, but it is still several times worse than the alternative of 21-49x.

The quality-based approach also leaves the door open to very concerning worst-case outcomes, especially if the US AI industry faces significant headwinds. To sketch an example scenario, it is plausible that Chinese companies will be much more successful at attracting users to their models, perhaps because the regulatory environment in the US turns hostile to AI. This could also coincide with US financial markets becoming disillusioned with AI, as they briefly became disillusioned with internet companies after the dot-com bubble. In such an environment, US companies may also struggle to obtain permits for new data center construction, even if the financing were there. If so, Chinese AI companies supported by state subsidies may be able to outspend and outbuild US companies, plausibly overcoming a 2x cost-effectiveness penalty to take the lead and start competing internationally.13

The CCP will not let Huawei fail

But at least the quality-based approach would suppress Chinese domestic AI chip production, because Chinese companies would stop buying Huawei, right? This might be the case if the CCP were free market absolutists, but alas, they are not: As even the administration’s White House AI & Crypto Czar David Sacks—a driving force behind the H200 policy—has acknowledged, China can and will “outfox” this strategy by mandating that Chinese AI companies also buy domestically made chips. They can calibrate these requirements to precisely match domestic production capacity, ensuring Huawei never lacks for customers regardless of how many US chips are available.

The reality is that semiconductor self-sufficiency has been a core CCP strategic goal at least since the Made in China 2025 roadmap, which was laid out in 2015, long before export controls. That roadmap set a target of 80% domestic market share for “high-performance computers and servers” by 2025.14 The repeated whiplash of US policy has only reinforced Beijing’s conviction that building an indigenous supply chain is a strategic necessity.

There is still time to change course

The administration’s recent rule falls between these two extremes: It puts a cap on the number of chips that can be sold to China while still allowing very significant quantities of exports. Under the current 50% rule, the cap sits at 900,000 Hopper-equivalent chips and rising over time—”over twice what China is expected to produce this year”. This would result in a US compute advantage of approximately 9-10x in 2026. The quality of the chips is also substantially higher than a strict quality-based approach would recommend. But the policy will still be less damaging than exports without any cap on export volume.

Fortunately, few if any chips have yet been shipped to China, and the administration is free to change its mind at any time. If it does, it would likely secure enduring US dominance in AI, plausibly causing a permanent collapse of the Chinese AI industry. But the details of how that would happen will be a post for another day.

Yes, I know, the rule also has a quantity restriction component. I'll get to that.

Throughout this piece I will loosely talk about “US chips”, but more precisely what I’m referring to are the overwhelming majority of AI chips that are designed and sold by US companies like NVIDIA, AMD, and Google, but are manufactured AKA fabbed in Taiwan by TSMC. These chips are subject to US export controls even if they never touch US soil, because of something called a “foreign direct product rule”.

Based on inference performance benchmarks showing the H200 delivers approximately 1.9x H100 performance while the Ascend 910C delivers approximately 0.6x H100 performance. At estimated prices of ~$32,000 for the H200 and ~$26,000 for the Ascend 910C, the H200 provides roughly 2.5x more inference performance per dollar.

This is more formally referred to as memory bandwidth (between the chip and its memory) and interconnect bandwidth (between the memories of different chips).

China’s total installed power generation capacity reached 3.35 TW at end of 2024, up 14.6% year-on-year, implying approximately 427 GW of new capacity added. By comparison, the US added approximately 30 GW of net new generating capacity in 2024.

In Epoch AI’s supercomputer dataset, the US holds approximately 75% of global GPU cluster performance while China holds approximately 15%, a ratio of roughly 5:1. Other estimates, such as Lennart Heim's, suggest a ratio closer to 10:1. The discrepancy may reflect different methodologies and definitions of "AI compute capacity", and limitations in Epoch’s coverage.

According to IFP’s analysis, which draws on SemiAnalysis and other sources, US AI chip production is projected to reach 6,890,000 B300-equivalents in 2026, while Huawei production is estimated at only 62,000-160,000 B300-equivalents—roughly 1-2% of US production. SemiAnalysis projects Huawei could produce ~805,000 Ascend units in 2025, but notes that HBM memory shortages will likely constrain actual output to 250,000-300,000 Ascend 910C units in 2026.

Experiments are estimated to make up a very large fraction, possibly a majority, of US AI companies’ compute use.

IFP analysis estimates the H200 achieves approximately 70% of the B300’s price-performance at FP8. Combined with footnote 3’s finding that the H200 is ~2.5x more cost-effective than the Ascend 910C, this implies the Ascend 910C achieves roughly 28% of B300 price-performance (0.70 / 2.5 ≈ 0.28). Separately, SemiAnalysis notes each Ascend 910C has “only one-third the performance of an NVIDIA Blackwell” chip. Given that Ascend chips are also cheaper (~$26K vs ~$53K for B300), this suggests price-performance of roughly 50% of Blackwell. Taken together, “one-third to half” is a reasonable if slightly generous estimate.

US hyperscaler AI infrastructure capex is projected to exceed $600 billion in 2026, with roughly $180 billion specifically on GPU/accelerator purchases.

Rough calculation assuming quality-based chips have 30-50% of Blackwell price-performance. Domestic production valued at 62-160K B300-equivalents × ~$53K = $3-8B (see footnote 7).

Lower bound ($30B spending, 0.3 price-performance): $30B × 0.30 = $9B Blackwell-equivalent, plus ~$3B domestic production = $12B total; US advantage = $180B / $12B ≈ 15x.

Upper bound ($50B spending 0.5 price-performance): $50B × 0.5 = $25B Blackwell-equivalent, plus ~$8B domestic production = $33B total; US advantage = $180B / $33B ≈ 5x.

Some combination of ingenuity and industrial espionage may also help Chinese AI companies make up for inferior compute with improved algorithmic efficiency.

The self-sufficiency targets come from the Made in China 2025 “Green Book” technology roadmap. See CSET’s English translation: Roadmap of Major Technical Domains for Made in China 2025, p. 8.